The Undisputed King of Kenyan Cuisine: How to Cook Perfect Ugali

If you walk into any home in Kenya around dinner time, there is a very high probability that a pot of water is boiling on the stove, waiting for the daily ritual of making Ugali. To call Ugali merely “food” is an understatement. For millions of East Africans, it is sustenance, it is culture, and it is the very definition of a complete meal. There is a common saying that if you haven’t eaten Ugali, you haven’t really eaten at all.

Despite its immense popularity, Ugali remains a mystery to many outside the region. Is it polenta? Is it fufu? Is it mashed potatoes? While it shares similarities with other starch-based dishes around the world, Ugali stands in a league of its own. It is dense, filling, and carries a subtle, roasted maize aroma that signals comfort to anyone who grew up eating it.

Whether you are a Kenyan in the diaspora missing the taste of home, or an adventurous foodie looking to expand your culinary repertoire, mastering this dish is the first step to understanding East African cuisine. For a complete breakdown of ingredients and a distraction-free cooking mode, you can jump straight to our Official Kenyan Recipes Page here.

What Exactly is Ugali?

At its most basic level, Ugali is a stiff porridge made from maize flour (cornmeal) and water. Unlike the soft, spoonable grits found in the American South or the creamy polenta of Italy, Kenyan Ugali is cooked to a firm dough-like consistency. It is solid enough to be cut with a knife, though it is traditionally pinched off by hand.

The flour used is typically white maize meal. You will find different grades in the supermarket:

- Grade 1 (Sifted): Very fine, white, and processed. It cooks faster and creates a smoother, lighter Ugali.

- Whole Maize (Kienyeji): This flour includes the husk and germ. It is darker (off-white), coarser, heavier, and packed with more fiber and a stronger corn flavor.

The texture is key. A perfect Ugali should be smooth, free of lumps, and firm enough to hold its shape, yet soft enough to be kneaded in your fingers. It serves as a neutral canvas, a vehicle to scoop up rich, savory stews, spicy curries, and sautéed vegetables.

The Cultural Significance of “The Mwiko”

Cooking Ugali is not just about mixing flour and water; it is a workout. The primary tool of the trade is the Mwiko, a sturdy, flat wooden spoon designed specifically for the heavy lifting required in Kenyan kitchens.

You cannot cook Ugali with a flimsy spatula or a whisk. As the mixture thickens, it becomes incredibly heavy and resistant. The cook must press the dough against the walls of the heavy-bottomed pot (sufuria) to crush any lumps and ensure the heat penetrates the flour evenly. This rhythmic mashing and folding action is known as kusonga.

It is often said that you can tell how good a cook is by the texture of their Ugali. If it is too soft, it is considered “porridge” and deemed a failure for dinner. If it is too hard or dry, it is unpleasant to eat. Hitting that “sweet spot” requires intuition, patience, and a bit of arm strength.

What to Serve with Ugali

Because Ugali has a mild, neutral flavor (similar to rice or pasta), it relies heavily on its accompaniments to shine. You would rarely, if ever, eat Ugali on its own. It needs moisture and flavor from sides.

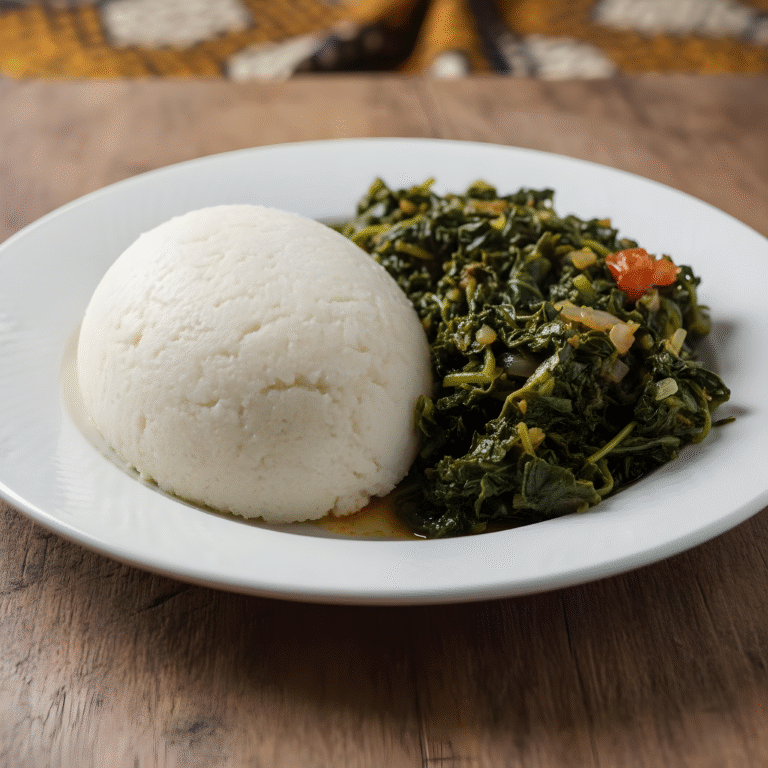

1. Sukuma Wiki (Collard Greens) The most iconic partner for Ugali is Sukuma Wiki. These thinly sliced collard greens are sautéed with onions, tomatoes, and sometimes a beef cube. The crunchy, savory greens provide the perfect textural contrast to the soft Ugali.

2. Nyama Choma (Roasted Meat) For celebrations, weekends, or family gatherings, Ugali is served alongside Nyama Choma (grilled goat or beef) and Kachumbari (a fresh tomato and onion salsa). The smokiness of the meat and the acidity of the salad elevate the humble cornmeal cake into a feast.

3. Sour Milk (Mala/Mursik) Among the Kalenjin and other pastoral communities, Ugali is often served with fermented milk. The sour tang of the milk cuts through the starchiness of the maize, creating a simple but deeply satisfying meal.

The Technique: How to Eat It

If you want the full authentic experience, put down the fork. Ugali is meant to be eaten with your hands (specifically, the right hand).

- Pinch: Break off a small, walnut-sized piece of the Ugali from the main mound.

- Roll: Squeeze it gently in your palm to form a smooth, round ball.

- Indent: Use your thumb to press a small depression into the center of the ball, turning it into a makeshift spoon or scoop.

- Scoop: Dip your “spoon” into your stew or use it to pinch some greens, and pop the whole thing into your mouth.

Tips for the Perfect Consistency

If this is your first time attempting Ugali, do not be discouraged if it turns out lumpy. Here are a few secrets from Kenyan kitchens:

- The Heavy Pot: Use a stainless steel pot with a thick base. Thin pots will scorch the flour before it cooks through.

- Boiling Water: Ensure the water is at a rolling boil before you start.

- Steam is Key: Once the flour is incorporated, you must cover the pot and reduce the heat. This steaming process cooks the starch in the center of the dough, removing the raw flour taste.

- The Smell: You will know the Ugali is nearly done when the kitchen fills with the smell of roasting corn. A slight crust might form at the bottom of the pot—this is prized by some and discarded by others, but it indicates the Ugali is cooked through.

Ready to start mashing? Cooking Ugali is a rite of passage. To help you get the ratios exactly right and track your cooking time, we have set up a digital kitchen companion for you.

👉 Access the Full Ingredient List & Interactive Method Here

Detailed Preparation Guide

While the concept is simple, the execution is an art form. Below is an overview of what you will need to do to achieve that classic Kenyan texture.

The Components You only need two things: Water and Maize Flour. Some modern cooks add a pinch of salt or a knob of butter/margarine to the boiling water, but purists insist on just the flour and water to maintain the authentic, neutral taste that pairs best with salty stews.

The Process

- Boil: You start with water. Let it bubble aggressively.

- The First Pour: You don’t dump all the flour in at once. You put in about half, let the water bubble over it, and stir to make a porridge base.

- The Build: You gradually add more flour, mashing continuously. This is where the work begins. You are looking for a transition from liquid to solid.

- The Steam: Once it is stiff, you gather it into a mound in the center of the pot and cover it. This steaming phase is non-negotiable.

- The Shape: Finally, you shape it into a round ball within the pot and turn it out onto a plate. It should slide out cleanly, holding its shape like a cake.

Conclusion

Ugali is more than just starch; it is the heartbeat of Kenyan dining. It is a dish that teaches patience and rewards effort. When you finally sit down to a steaming mound of white Ugali, paired with a rich beef stew or vibrant greens, you are tasting the true soul of East Africa.

Don’t be afraid to put some muscle into it. Grab your wooden spoon, boil your water, and bring this delicious tradition into your home tonight.

Click here to view the recipe card and start cooking